Martin Eden: Bibliography of Secondary Sources

The Valley of the Moon: Bibliography of Secondary Sources

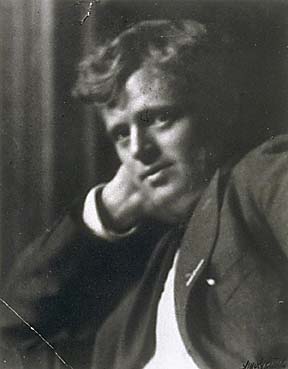

A short description of London from The Book of Jack London

Jack London at work

Jack London's Ranch: Photographs is a set of pictures from his home in Glen Ellen, California

Jack London and Wyatt Earp meet Raoul Walsh (pdf format) From Walsh's Each Man in His Time: The Life Story of a Director (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974, pp. 102-104). Note: Leonard Maltin describes this book as "entertaining fiction with an occasional nod at the truth."

The Jack London Society website includes current information about what's happening in London studies.

The Jack London Online collection, formerly at UC Berkeley and now at Sonoma State University, is one of the best author sites anywhere on the web. Containing HTML versions of London's works, photographs, biographical information by noted London biographer Clarice Stasz, a list of Jack London's works by date of composition by Jack London Journal editor James Williams, image files of documents, and bibliographies, it is an essential stop for students and researchers working on London.

- The Jack London Story and the Beauty Ranch (here in text format) is a fascinating oral history project that includes interviews with Milo Shepard, Sara S. Hodson, Jeanne Reesman, Waring Jones, and Jacqueline Tavernier-Courbin.

- The Huntington Library is the major repository for Jack London's papers and is an essential stop for researchers working on London.

- Utah State University Library also has an extensive Jack London collection.

- Article on a recording of Jack London's voice: "The voice of the famed author can be heard in a 2½-minute recording, the only recording of London known to exist. It was made almost a century ago and just now recovered from a wax recording cylinder." (Thanks to Clarice Stasz of the Jack London listserv).

- The Jack London Collection includes screen shots and transcriptions of letters and screen shots of manuscripts.

- Jack London State Historical Park. This site (from 2005) contains a biographical sketch and current pictures of London's Beauty Ranch.

The Jack London International Site offers an international perspective on Jack London, with essays by the editor, Reinhard Wissdorf, and such notable London scholars as Dr. Vil M. Bykov. It features materials in English and German, including a timeline, interviews with Jack London, a biographical sketch, pictures (including a slideshow with music), and a discussion list. George-Sterling.org is a site devoted to George Sterling, a California poet and London's closest friend. The site includes his poems, a tribute by Jack London, and several articles on Sterling, London, and the California Bohemians.

The

God of His Fathers and Other Stories (1901;

stories)

Children

of the Frost (1902; stories)

The

Call of the Wild (1903)

The

People of the Abyss (1903)

The

Sea-Wolf (1904)

White

Fang (1906)

Moon-Face

& Other Stories (1906; stories,

including "All

Gold Canyon")

Before

Adam (1907)

The

Iron Heel (1908)

Lost

Face (1910; stories, including

"To

Build a Fire")

Burning

Daylight (1910)

Adventure(1911)

Martin

Eden (1913)

John

Barleycorn (1913)

The

Valley of the Moon (1913)

The

Star Rover (1915)

The

Red One (1918; stories)

from The Book of Jack London, vol. 2, by Charmian London (New York: Century, 1921), 219-221.

Our main meal was at 12:30. This hour better

suited our work and Ranch plans generally. At twelve the mail-sack--a

substantial leather one bought before we sailed on the Snark--arrived

at the back porch, and Nakata brought it to me to sort the contents.

In the half-hour before dinner, Jack had glanced over the daily paper,

read his letters, indicated replies on some of them for my guidance, and

[219] laid the more important ones in their wire tray, one of many such

nested on a small table beside the Oregon myrtle rolltop desk where he

transacted business. I always endeavored to have his ten pages of

hand-written manuscript transcribed--an average of two and a half typewritten

letter-size sheets--before the second gong (an ancient concave disk of

Korean brass) belled the fifteen-minute call to table. Jack implored

me to be on time to the minute's tick, and attend to seating the guests,

so that he might work to the last moment.

In many minds,

I am sure, still lives the vision of the hale, big-hearted man of God's

out-of-doors, the beardless patriarch, his curls rumpled, like as not

the green visor unremoved, pattering with that quick, light step along

the narrow vine-shaded porch, through the screened doorway and the length

of the tapa-brown room to his seat in the solid red koa chair at the head

of the table. "Here comes a real man!" was the prevailing sentiment.

How he doted upon that

board with its long double-row of friendly faces turned in greeting, ever

ready with another plate and portion! It was his ideal--carried

from old days with the Strunskys'. "In Jack's house," one writes me, "I

met the most interesting people of my life and of the world." And

perhaps, while we fell to our portions, before his own was tasted he would

read aloud newspaper items or newly received letters; or he might launch

out in a fine rage of his eternal enthusiasm, upon some theme that claimed

him, or strike into argument, whipped hot out of his seething brain and

heart. Always there was in him the potent urge to gather all about

him into knowledge of whatever claimed his attention. Years only

added to his capacity to function in every potentiality. There were

no numb or inactive surfaces in his make-up, mentally, physically.

He reached in all directions, to play, to work, to thought, to sensation.

His face, smiling, cracked with thought-wrinkles, weather-wrinkles, laughter

wrinkles. [220] At no time did he have more than a few gray hairs; and

his hands, to his pride, were very firm, showing no dilated arteries.

"One is as young as one's arteries," he was fond of saying. . . .

Many were more impressed

by his eyes than any other feature or characteristic. . . . They were

eyes that look into one, and through and beyond--as if what they saw on

the surface, in one's own, led his into the deeps behind, into the brain,

conscious and unconscious and far behind again into the intelligence of

the race down through all the drift of the human. Gray, or iris-blue,

they were when mild, the large pupils giving them a splendid, brilliant

darkness; but let him be angry, instantly they went cold, metallic, the

enormous pupils narrowing to bitter points. [221]

"A Hero to His Valet" by Yoshimatsu Nakata, transcribed by Barry Stevens (Jack London Journal 2001): 26-103.

After he dressed, Mr. London would start to work. He had a certain way of writing, and it was the same every day. He has a cigarette in his left hand and a blunt fountain pen with a wire tube at the end--a stylograph. He always used this instead of a fountain pen. The idea is that he doesn't have to watch the nib to see if it is turning to one side. When he is writing he is always humming something or singing. It is called "Redwing" [words here; sound recording here].He played that all the time on the phonograph on the Snark, and at home he still hums and sings it. Then he puffs a cigarette and writes some more and he does that for twenty minutes and then he gets up and takes a drink of Scotch whiskey. Then he eats a Japanese fish, the small white dried fish called creme iriko that they use for bait. He eats that once in a while and then writes. Every twenty minutes he counts the pages. he writes so big, I suppose there are a thousand words to about twenty pages. After he writes about an hour, he begins to count and then writes about twenty minutes again. About four or five times he does this, and then he figures he is finished with his work. (36-37)